A.I. Detectors are the New Polygraph:

AI Detectors: The new polygraph machine costing universities, failing innocent students, and preventing student learning while failing to work as advertised

Part 1: Who Watches the Watchmen?

We know that students are using ChatGPT to cheat (Bulduk, Papa, & Svanberg, 2023). My recent study demonstrates that teachers can be trained to detect AI to catch plagiarism in the classroom (Fortson, 2023). In a world in which AI-detectors already exist, why should we train teachers to recognize the signs of AI, rather than outsource the skill to a machine?

Imagine a university student named Hana. Hana is facing the threat of expulsion for academic dishonesty due to plagiarism. The University’s plagiarism software returned a claim that the paper was written by ChatGPT, but Hana swears she wrote the paper herself. “I have rough drafts—edits. I spent hours on this paper. I didn’t use AI, but the university is relying on the report of their AI detection. They claim it’s accurate, and now I might not be able to get my degree. I might get kicked out of college, and I have no way to prove to them that the AI detector is wrong. They don’t even have any proof. They don’t even know what the report means. They just have a report by an AI detector.”

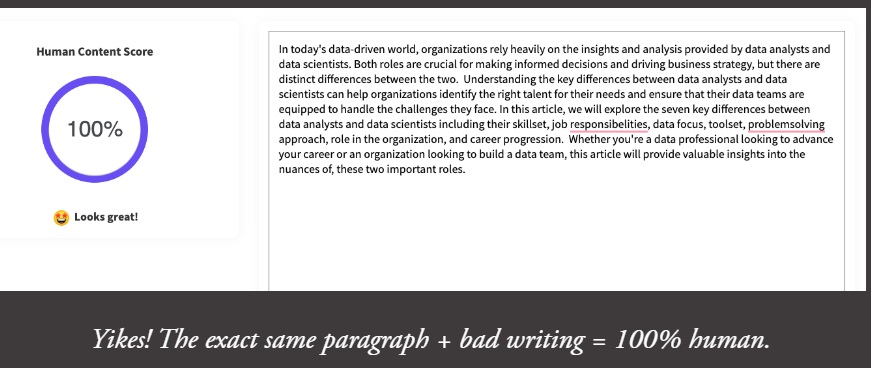

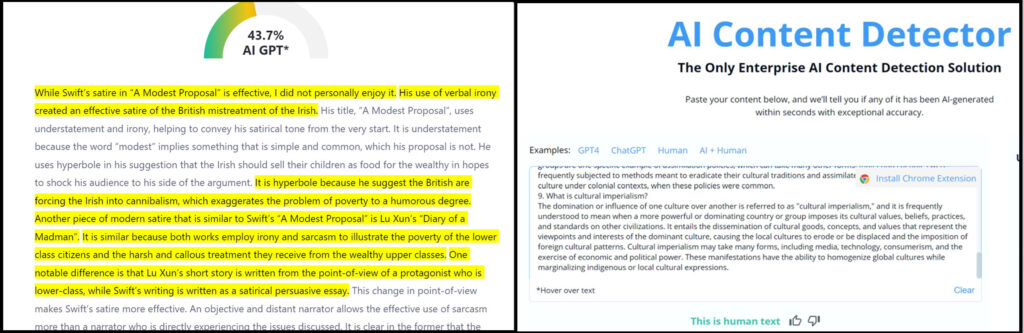

On the left is a false positive score from “AI Detection Software”; A human wrote this, yet AI says it was written by ChatGPT.

On the right is a False Negative score from “AI Detection Software”; ChatGPT wrote this, and yet AI says it was written by a human.

Many a professor has found themselves lost as to what to do in the face of ChatGPT in regards to academic integrity. “All my techniques to make sure students were doing their own writing no longer work against AI. I have no choice but to rely on Turnitin’s AI percentage. It’s our school policy,” a teacher I interviewed says. It seems that teachers have had to trust modern day electronic shamans: an unknown algorithm—a ghost in the machine—that claims to detect the computer-written word. But when even ChatGPT is known to “hallucinate” facts and sources (hallucinate being a term for the tendency for ChatGPT to makeup things that do not actually exist), how can we trust the verdict of an AI to find the same crime it’s accused of committing? The truth is: we can’t.

Part 2: Harrison Bergeron Goes to Harvard

The immediacy of the effects of AI in the academic world have been swift. English teachers lament the death of the essay because they have no way to check for plagiarism in the face of AI. In the face of this threat, many universities have turned to AI detection software. Some professor’s merely ask ChatGPT if it wrote an essay and accidentally fail innocent students (Klee, 2023). However, these professor’s do not understand what ChatGPT is (Zaza & McKenzie, 2018): It is not truly an Artificial Intelligence. It is a language predictor based on the statistics of word frequencies—and advanced version of the predictive text your email and SMS uses. I’ve written essays and asked AI detectors if it was AI-generated, only to be told the paper I literally just wrote was actually made by a machine. I’ve had ChatGPT write an essay and run it through AI detection only to be told it was 100% human. This issue is even more likely to affect ESL students, who’s writing lacks the “burstiness” and “perplexity” supposed “AI detection software” is trained to detect (Liang, Yuksekgonul, Mao, Wu, Zou, 2023). Are we in the Matrix? Is ChatGPT hallucinating, or am I?

Professors who are relying on ChatGPT to check itself are giving too much faith to the very machine they are raging against. But what of universities with a little more understanding of ChatGPT’s limitations who opt to pay for subscriptions to AI detectors instead?

The problem is that numerous innocent students, like hypothetical Hana, become accused and condemned due to the AI’s “hallucinations”. Most of the professor’s using AI detection don’t even know what the algorithm is checking for.

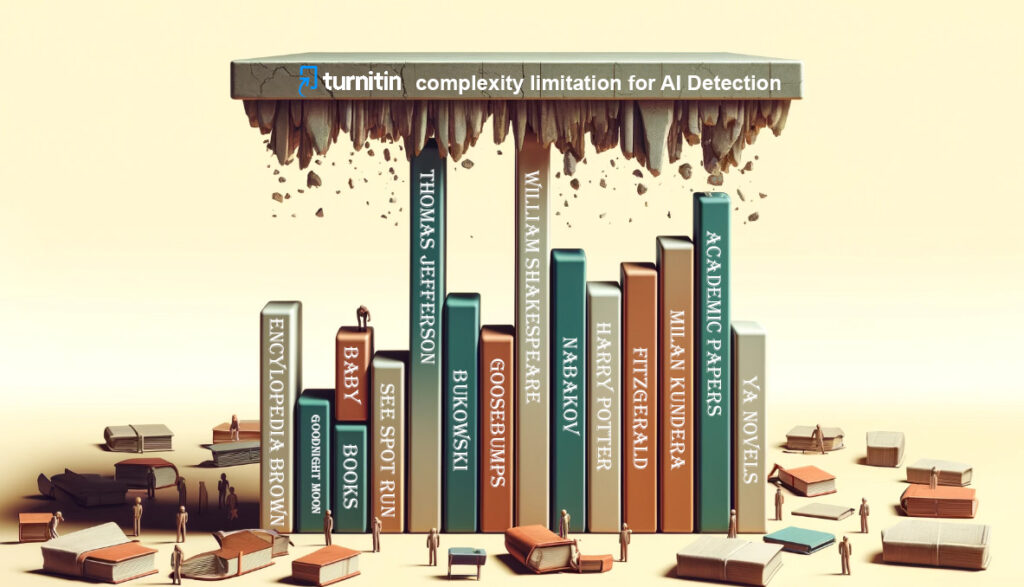

“Grammar mistakes,” one student says. “If you write too perfectly, it can become flagged as AI. AI detectors will say documents written in the style of Thomas Jefferson are AI because of the long sentence structures with tons of commas. If you are worried that your original work will be accused of being written by a computer, just throw in some comma splices and misspell a few words. Maybe rephrase something more poorly. Simplify your work.” From, “When in the course of human events…” to “See Spot run.” To beat the machine that checks for a machine, we dumb ourselves down. Where do we go when even Harvard goes Harrison Bergeron?

by so-called “AI detection software”

It’s deeply ironic that educational institutions aimed at teaching students how to write their best are now, inadvertently, causing the best students to purposely write poorly to avoid false accusations of AI-generated content. It’s even more ironic that as a society fearing human work done by AI, we’ve turned to AI to check itself. A recent episode of South Park depicted an AI detector as a shaman resorting to mysterious techniques akin to reading tea-leaves. And it’s true: If you rely on AI detectors, you may as well ask the stars whether a paper was plagiarized (or if Pisces is rising). But this is not a battle that can be won by fighting fire with fire. Just like John Henry, a latter-day luddite saint of sinew and human spirit, who stared into the gears of the coming industrial revolution and forced the machine to flinch, it will be man that defeats the machine.

Part 3: More Human Than Human

My recent study demonstrates that teachers can indeed be trained to detect AI-written work by learning forensic linguistics, which is the same methods used to catch Ted Kaczynski, the Unabomber; this is combined with reverse prompt-engineering, which is learning how to decode what specific prompt someone would have given ChatGPT to generate a response to prove conclusive evidence of plagiarism. In my recent study, teachers took a pre-assessment involving a mix of human-written and AI-written papers. After receiving Professional Development on AI detection, teachers improved their ability to detect ChatGPT by over 67%, and improved their ability to spot Quillbot by 60% (Fortson, 2023).

It was pure synchronicity that I had my tenth-grade class read Huxley’s Brave New World this year to have a discussion about a society that had hoped technology would bring them utopia yet found themselves the complacent consumers of a world created around them, and not by them, through science—a world in which man no longer uses his tools, but the tools use him. This is nothing new: The idiom that, “To a man with a hammer, every problem looks like a nail,” implies that ever since the wheel, technology acts on us, changes us, as much as we act on it. What will ChatGPT do to us? I don’t mean to sound apocalyptic when I tell you that, in one of my assigned essay prompts, I had students compare the themes in Brave New World with Matt Judge’s 2006 comedy Idiocracy.

I’ve seen a plethora of attempts at plagiarism in my tenure. I say attempts because I’ve always prided myself on catching my students when they tried to cheat. Students usually figured out in the first few papers that things don’t get by me, and so they stop trying to cheat and start trying to learn.

But ChatGPT changed that. Faced with a technology I didn’t understand, a technology that felt more powerful than the skills at my disposal, I first turned to hand-written paper essays. It seemed to work, turning back the clock of time, and I hoped that having students write their answers with pen on paper would prevent their copy-paste strategy. And this is when I discovered how deep the rabbit hole went.

Part 4: Go Ask Alice

“Alice” is an ESL student I had last year. As I read Alice’s paper, I felt in my heart an ounce of pride and a dash of shame. Here was a student who was failing my class—she’d barely turned in any assignments the whole year, and many of the ones she completed were copy-paste jobs. At best they were “Franken-essays”: Essays stitched together out of quotes from various sources with no ounce of her own writing to serve as the meaty mortar between them, even if there was a Works Cited page included. I told her class how much I enjoyed films about con artists because I felt a begrudging respect toward them: They were liars, but they were good at what they did—The meticulous planning, research, and skill with which they operated was unethical, but it was not lazy. It required thought and effort. It was not just copy-pasting the first search result from Google. “They’re con artists,” I’d say. “Don’t disrespect the art.”

“Besides,” I’d continue, “it’s better to get a B with your words than aim for an A you didn’t write and end up with an F for plagiarism.” Begging for students to engage in the Nash equilibrium fell on deaf ears. They were too busy watching the next TikTok reel the algorithm had summoned before them on smuggled phones that they weren’t supposed to have in the classroom.

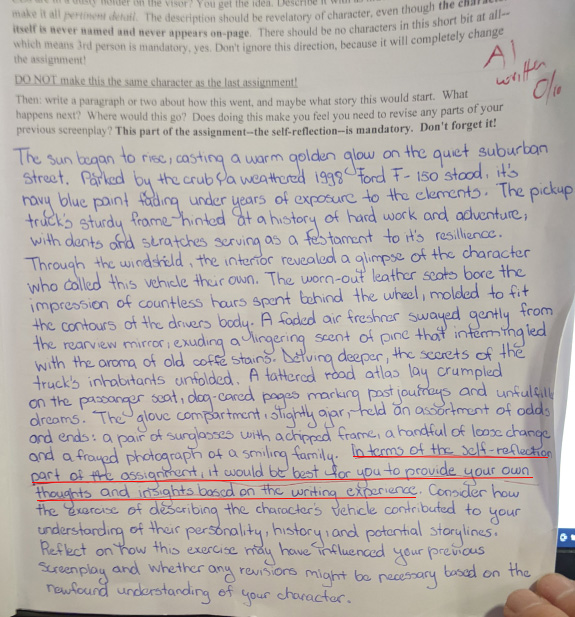

But this assignment was different: Her descriptions were so elegant for a high schooler—the language so skilled—that I felt proud for what she had written. Then I came to a sentence in her reflection paragraph in which she was supposed to describe how she felt the writing process went for her. There was no wrong answer for this part of the assignment. Any student who turned in the assignment would receive full credit. The student had mocked me, and my heart had lied, and on her hand-written paper, these words appear: “In terms of the self-reflection part of the assignment, it would be best for you to provide your own thoughts and insights based on the writing experience.”

She was not a Harper Lee merely hiding behind apathy. She didn’t even notice what the sentence she had copied meant (let alone the abrupt shift from first to second-person). She had bowed before the algorithm and put her faith in it completely. As I continued to grade other students’ workbooks, I began to feel a sense of déjà vu: phrases vaguely remembered from readings before; new words but syntactically arranged in the same order. Sometimes the car was red, sometimes it was blue, but it was always faded. Why did nobody create a character with a new car? Or a van? Why was it so often a Ford 1-50? Did the kids even know what that was? They mostly talked about Andrew Tate and Bugattis…

After reading thirty papers, I had a good sample size to notice I was being served the same thing over and over like Sisyphus. Something didn’t sit right, but I couldn’t prove plagiarism, because nobody had copied from an existing source on the web or in print and the AI software had not detected plagiarism in most of them.

Then I had an idea. There’s a reason Catch Me If You Can’s Frank Abagnale was hired by the FBI to catch counterfeiters: If you want to catch a crook, you need to think like a crook.

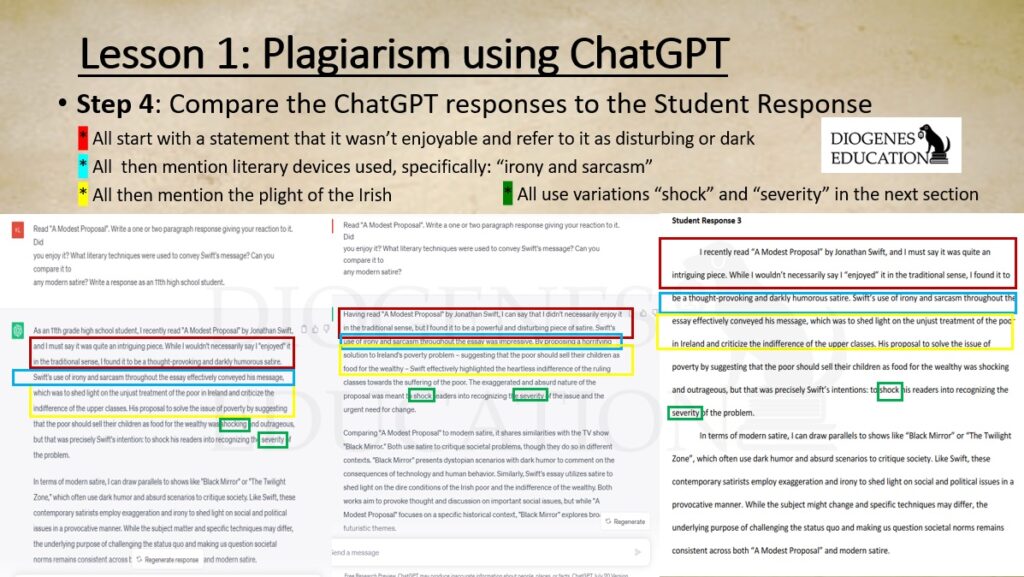

I opened ChatGPT and typed in the question I had given the students. And there it was. The same answer I’d read so many times grading these papers. Sometimes students wrote that the sun cast a golden glow, other times a golden hue, but it was the same story, the way a movie on Lifetime or The Hallmark Channel is merely a palette swap—Campbell’s Hero with a Thousand Faces now as blurred as the very same early AI attempts to draw them were.

But many of the AI detectors continually returned these stories as being human-written.

Another student, Dorothy, wrote her own essays. I know this because I watched her writing in-class essays for the whole year. As an ESL learner, there was an obvious stilted manner to her prose. There were ideas in her head that the vocabulary at her disposal couldn’t form in a sophisticated manner, and her writing took on the monotone, syntactically similar prose of an artificial intelligence Large Language Model (LLM). And because of that, AI detectors suddenly started accusing her of AI-writing, though she had been writing her own work. ESL students’ writing is more likely to be falsely accused of being AI by AI detectors, and there is a deep irony in trusting the police to police itself. Can we trust AI?

No, detecting AI is something only a human can do. But the rabbit hole went deeper.

Part 5: Simulacra and Simulation: An AI Hall of Mirrors

In my IB Individuals & Society course, I felt the same déjà vu. In my mind I was hanging red string between words and facts looking for Pepe Silvia. The student answers seemed to mirror ChatGPT: Though the words were different enough, the robotic finger prints were there.

Every author has a unique voice—a writing style that is their own, with unique patterns of punctuation, or fixations on certain verbiage or figurative language. You can see a Spielberg film and know he made it. David Lynch has his own diction and Quintin Tarantino has his. Miles Davis has his and The Germs have theirs. Whole genres and mediums have developed “languages” unique unto them. We refer to the “lexicon of film” or the “lexicon of jazz”. ChatGPT also has its own lexicon. But the (lexicon) devil is in the details.

After you read enough papers, you begin to understand “ChatGPT voice”: It is a certain phraseology; a certain organization. It becomes its own genre with its own standards and tropes as much as a Western or a YA novel stories have theirs. If you watch enough Detective movies, you know that it’s going to be the butler who did it, and the clues foreshadowing the reveal that a novice to the genre overlook become beaming spotlights to the initiated

As I read the response, I had the impression of a robotic ventriloquist using this student as a dummy, moving his lips and speaking through him—the student an empty vessel—Pinocchio before the blue fairy.

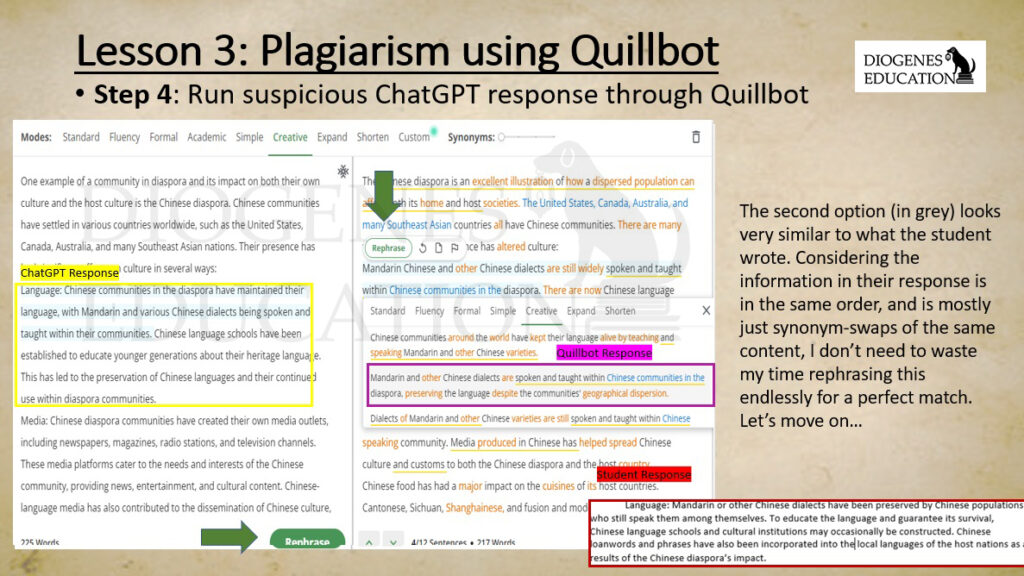

The problem was that Turnitin did not detect AI. And Grammarly did not detect plagiarism. I knew the truth, but I could not prove it beyond a shadow of a doubt. I believe in fairness, and I would never accuse a student of plagiarism without a smoking gun like so many previous professors had. Better that one-hundred guilty go free than one innocent be falsely judged. When I asked ChatGPT the same prompt, there were familiar elements, but not enough to remove the veil of uncertainty. Do I mark him for academic dishonesty, killing his chance for a good grade? Do I move on and grade other papers? I copied ChatGPT’s answer, and ran it through Quill Bot.

Quill Bot is another “AI” software that will paraphrase any text you give it and can change the percentage of paraphrasing and the complexity of the synonyms used, even simplifying text to different grade levels, or adding more figurative language, depending on how the settings are tweaked. Author Tim Robbins said, “There is no such thing as a synonym. Deluge is not the same as flood.” But do my students know that?

Quillbot now allows students to use ChatGPT and hide their fingerprints by synonym swapping and simplifying and distorting the original so much that the computer itself doesn’t know it wrote its own work as it stares at itself through a mirror darkly.

But my students will not be writing book reports on Shakespeare as adults. So, who cares if they use ChatGPT and get away with it? What does it matter?

Part 6: All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace

So why does it matter?

The old adage was that we’d never have a calculator in our pocket, so we better learn our times tables. But now we do: In every smart phone—in every pocket.

“I think we should be letting the kids use ChatGPT as a resource and teach them how to use it,” a parent with school-aged children tells me, referencing the calculator analogy. The problem with the analogy of calculators and language predictors is that a child that uses a calculator is still forced to learn that 2+2 = 4, and not 5.

I do believe there is a place for ChatGPT, just as there is a place for calculators. I told a student that they needed to hide their information from ChatGPT. Ask it a question. Then, Google that information to find another source that says the same thing. Then, they can write their own response using that verified source. I compared it to money laundering: You used ChatGPT, an illegal move, but you went and washed it clean with another verified source. My students love Breaking Bad, so the idea that they were operating their own meth-lab/car wash scheme via academics made them feel as if they were getting away with something; however, all I ever wanted them to do was read multiple sources and compare information and know how to verify facts: Read one source, trace it back to a primary source, look for bias, contrast the information with other sources on the same topic and look for verification or omission. This is what I, as an educator, want.

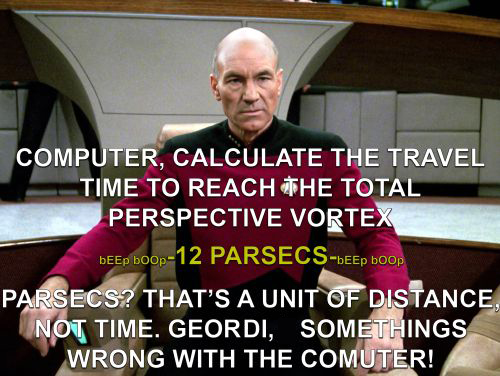

But what happens when a student doesn’t know why their answer is right or wrong? What if they merely rely on a fallacy of authority to the Artificial Intelligence and the automatic answers it gives, as was the case at first with “Alice”? Students that cheat overestimate their own abilities (Chance, Norton, Gino, & Ariely, 2011), perform lower on summative tests (Arnold, 2016), and are more likely to be dishonest in their adult occupations (Brodowsky, Tarr, Sciglimpaglia, Ho, 2019). Do we want engineers who can’t spot a mathematical error on their calculator? Or do we want scientists who, just like in Star Trek, can critically think about the answers the machines give them, and even question them when the computers are wrong?

This is why we should care about AI plagiarism. This is why we have to use the correct methods to police plagiarism in schools. A student can’t learn about how to find good sources, or how to read, or how to write, by copying answers from ChatGPT. He cannot become educated. He cannot become intelligent. He can only mimic intelligence by parroting information received from somewhere without a thought of his own. Much like what ChatGPT itself does. In essence: The student becomes an organic Artificial Intelligence all its own, and the ouroboros is complete. Nobody thinking, just an endless loop of unwritten and unread content: forever. Once we trust blindly in the machine, we are in a brave new world of automatically generated content with no thinking required.

It’s a future that universities and high schools are no doubt also frightened of, which is why they’ve tried to stop the tide of AI writing with AI detection software that, as we’ve seen, doesn’t work. ChatGPT Zero has stopped their operation due to its inability to perform as required (Blake, 2023), and Turnitin needed to make statements about their own unreliability in certain contexts (Chechitelli, 2023). This is why I propose we should be educating the educators about how to detect AI plagiarism—not with some other AI, but with these techniques—and if academic institutions cannot do so themselves then they should hire those who can detect plagiarism and not trust blindly the very machine they are fighting against.

Will we adapt? Will we learn? As academic institutions spin their wheels in desperation, students like Hana and Dorothy have their future held hostage by wrongful accusations, and students like Alice trust blindly in the authority of the AI. But aren’t the professors blindly holding students like Hana hostage on the basis of a computer report doing the same? The way forward is clear. The question is, what will schools do about it?

Part 7: The Rest is Still Unwritten

And so it goes…

…

Download the FREE introduction to A.I. Detection Professional Development HERE

Get Started With AI Lessons in Your Classroom

Artificial Intelligence AI ChatGPT Research, Descriptive and Figurative Language

Catch Cheaters: Artificial Intelligence Plagiarism detection: ChatGPT Professional Development

Read how teachers can succesfully use AI: 10 ways to use AI in the Classroom: Beyond ChatGPT

Get a FREE SAMPLE of our lessons at our online store