Comic Books in the Classroom:

Should Your Class Read a Graphic Novel?

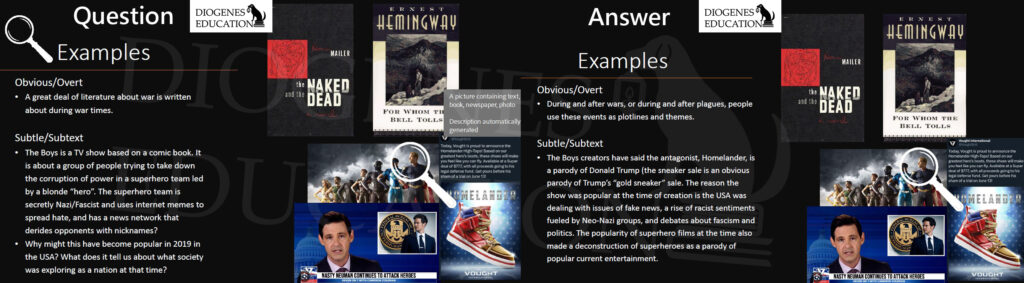

Comic Books are often associated with immaturity, not literature. But can teaching graphic novels be beneficial for students? They can, and in today’s multimedia landscape, part of a Media Literacy Unit is understanding image analysis. This is why the IB curriculum, whether it be the MYP or DP track, teaches students the skills to do an IB Image Analysis, including the ability to, “Make inferences, analyse the picture, interpret it, …[and] present their findings in the form of an essay.” I use The Watchmen for reasons I’ll explain below. So, why should you teach a comic book?

Because it turns out: A large portion of the audience of another superhero deconstruction narrative, the Eric Kripke-helmed adaptation of Garth Enis’s The Boys on Amazon Prime, didn’t understand the message either.

Schools Should Teach Media Literacy

“The Boys went woke!” detractors post online. How did they miss the glaring symbols in the show that Homelander was supposed to represent Trump, and that the show’s message was always pro-DEI and inclusivity and both anti-corporate and anti-fascist? It is because of the same ignorant cry that errupts when people analyze any media: that, “It’s just a movie, you shouldn’t think too deep,”–the declaration that blue curtains must represent nothing but blue curtains–that continues the brain-rot of The Boys‘ fanbase. Students need to understand that art is not created in a vacuum. Art is a dialogue. Art tells the temperature of the time period it was created. These are things deeply analyzed in New Historicism Units. But students, despite consuming more media than ever, understand it less and less. When students are spending almost seven-and-a-half hours in front of a screen viewing image after image, they need to learn what those images mean. The best way to teach the symbolism and subtext of images is with a Graphic Novels Unit.

Prepare Students to Understand Symbolic Language

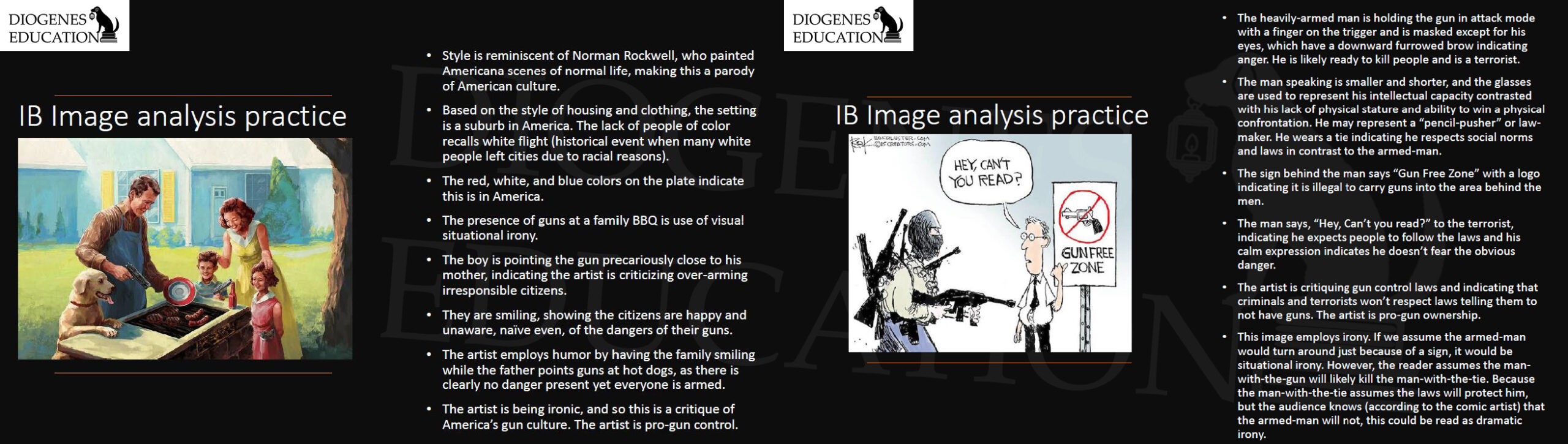

When I presented these images to my students in a Satire Unit, prior to doing a Graphic Novel Unit, students answered that the joke in the first comic was, “He’s shooting at sausages, and the sausages are unarmed, so he’s a foolish man”. They answered that the second comic, “Is a joke because the man probably can’t read because he’s bringing guns into a gun free zone and so he can’t read the sign.” No wonder fans of The Boys didn’t get it: Media Literacy is under-taught! I hope to remedy that in my classroom. I hope you do, too.

We had to go through the images carefully and discuss its component elements, as demonstrated for the second of the two gun-debate comics:

- What is the expression on the man with the gun? (He looks angry, as indicated by his furrowed brow).

- How is he holding the gun? (It is in his hands with the finger on the trigger, indicating he is ready, or intends, to use it).

- How is the man pointing to the sign depicted? (He is smaller than the other man and wearing glasses and a tie. Glasses are usually symbolic of wisdom, but not fighting, so will the angry man with the gun be stopped by this man?).

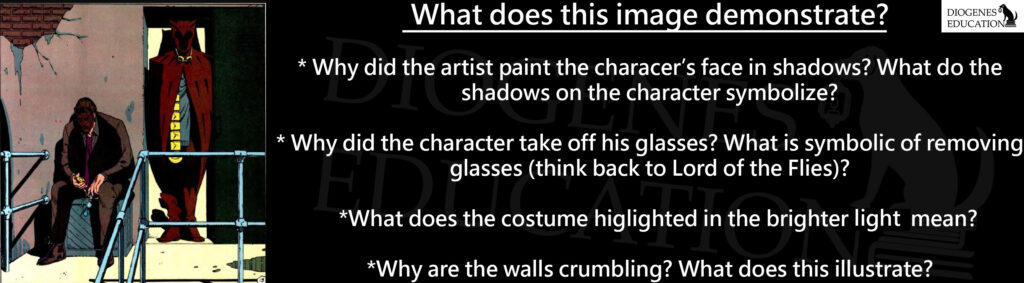

We had to put the pieces together like a puzzle–pieces the students didn’t even register as important–to understand the author’s point-of-view in the political cartoons. These are skills that were strengthened through a Graphic Novel Unit. My class read The Watchmen–which was fitting, because it turns out every frame was carefully considered when it was inked.

Alan Moore and The Watchmen in the Classroom

Before reading and analyzing The Watchmen, students learned that art (good art, anyway), whether it is a movie or a painting or a book, is intentional. I show them how directors put subtle background details in films, like the books becoming blank in the background of the bookshop as Jim Carrey’s character begins losing his memories in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind.

We analyze art and research the time period to understand the meaning of famous paintings. We begin with a video from The Nerdwriter analyzing The Death of Socrates.

We design danger symbols for the distant future and write persuasively using ethos, pathos, and logos to make a case for why their design is the most effective. Students analyze how scenes in books and movies differ, understanding Heideggar’s hammer, or the concept of a story affecting us based on the medium it is expressed in, which is encapsulated in our debate on Francis Truffaut’s statement that, “There is no such thing as an anti-war movie.” Students learn that images and words in texts are not random, but intential, and therefore have intentional meaning. Once they understand that, they can figure out what that meaning is. They can do it, they just need someone to show them the way. As a teacher, that’s where your job begins.

Get Started with Media Literacy Units in Your Classroom

Graphic Novel as Literature: IB Image Analysis, TOK, The Watchmen

Media Literacy & Fake News: Primary & Secondary Sources, Bias, Reliable Sources

New Historicism: Lesson, Media, and Assignments

Satire: Irony, hyperbole, understatement, & parody RL.11-12.6 RL.8.6 RL.8.5.A

Get a FREE SAMPLE our Comics/Graphic Novel lessons with a The Watchmen PDF lesson