Why Can’t ChatGPT Make a Full Glass of Wine? Using ChatGPT for IB TOK and Psychology

Ask ChatGPT to make an image of full glass of wine. Half-full right? Ask it again, but be more specific: Make a glass of wine filled to the brim that is about to spill over the edge. Still half-full, right? Why can’t AI make a full glass of wine? Well, this half-empty glass of wine is an excellent opportunity to engage in a discussion about knowledge, examining cognition, prototypes, schemas, and cultural bias in a unit for Psychology and IB Theory of Knowledge classes, turning this AI-half-empty-glass into a glass half-full situation.

[Note: as of March 26, 2025, ChatGPT can now make an image of a full glass of wine. So, if we follow the steps below, we can ask: what does ChatGPT know that it didn’t before?]

Teaching IB Theory of Knowledge and Psychology With ChatGPT

I promise to tell you why ChatGPT can’t make a full glass of wine by the end of this blog, but for now: let it marinate in your mind. I’ve written before about ways to use AI in the classroom that are process-based and not product-based because I am generally opposed to letting students use AI for their writing. Why? I recently received an email from a student in which they explained why they couldn’t come to my advisory to redo an assignment. The email ended with a bracketed [insert your name here]: They had used ChatGPT to write the email, and hadn’t even bothered to read the output! The great irony is that the reason they had to make-up an assignment for my class in the first place was because they had used ChatGPT to write their assignment for them (a choose your own adventure story in a post-modernist style). The greatest irony? The student told me that another teacher had advised them to use ChatGPT to improve their writing. Like a split-brain patient with a severed corpus callosum, the left hand does not know what the right hand is doing. Do they know why this is bad advice?

Most students aren’t reflecting on why the AI gives the response it does, and often don’t even read it, resorting to a CTRL-C/CTRL-V strategy. Imagine a student asks an AI to, “Fix all the grammar mistakes in my essay.” The AI will do that… but do the students then go through the process of seeing the error, figuring out the mistake, and correcting it the same way they do when they see the error highlighted in red pen on their paper? I think we must admit that, in this case, they are not going through the learning process. As educators, don’t we care about process, not product?

People often like to erroneously compare AI to the calculator, but even then: Would you recommend a PYP student use a calculator to do their adding and subtracting homework before they learned the basic principles of addition and subtraction? Sure, the tool gets the result, but what is our focus? We aren’t building Mechanical Turks (save that for your MYP Design class). If a PYP student can solve a calculus problem on a calculator but doesn’t know why they got the answer, then our students will just appear to have knowledge yet have none, like those in Searle’s Chinese Room. I suspect many of you teachers are guilty of this as well. Why, you ask?

John Searle and The Chinese Room

ChatGPT’s latest upgrade to “be more friendly” was interpreted to mean “write with thousands of emojis like a teenager’s Snap Chat.” And now, LinkedIn, a site supposedly for professionals, is full of rocket ship bullet points (ChatGPT’s current favorite obsession). Did any of the so-called professionals stop to look at what ChatGPT had done to “improve” their posts? It’s like leaving the house for a job interview and not realizing the mustard stains on your shirt. The issue is that people are not reading the output from ChatGPT, like Searle’s Chinese room in which someone follows instructions to produce Chinese text without knowing what it says. And honestly, why are we suggesting students use ChatGPT to “improve their writing”, anyway? Has anyone ever once read something from ChatGPT and thought, “Wow, this is truly a stunning piece of prose worthy of emulation,”? And emulators are all we and the students will be if we aren’t careful. I’ve written previously about how students would hand-write a response from ChatGPT and include the “as a large language model, I am unable to…” in their paper, which is why whatever you use ChatGPT for in the classroom: make it as far removed from what you will be grading as possible. If you are grading writing, use ChatGPT only as an image generator, and have students write the reflection on why the ChatGPT created the image based on their prompt engineering efforts.

Writing Reflections Using Image Generators

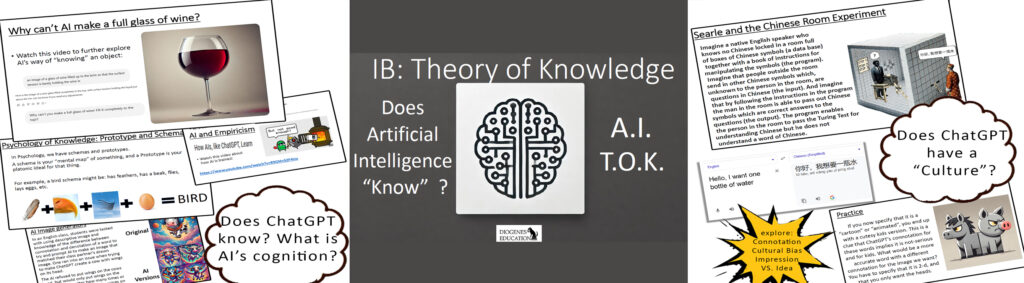

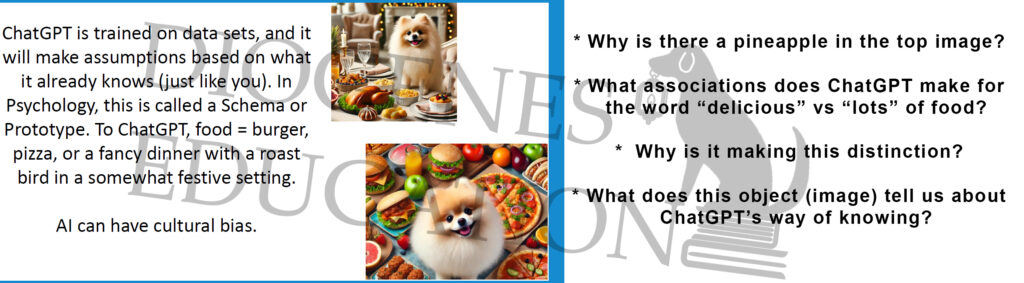

Ask ChatGPT to imagine a Pomeranian with lots of food. As of now (February 2025), it creates a Pomeranian surrounded by burgers and pizza. Why, I asked my mostly-Egyptian audience, does it not imagine koshary? Well, there are more English-speaking countries than Egyptians, and AI (which is more accurately called a Large Language Model) relies on the statistically most likely answer: Burgers are a more statistically likely food than koshary. Then why, with the billions more Chinese-speaking people, does it not imagine a Pomeranian chowing down on chicken feet and hot pot?

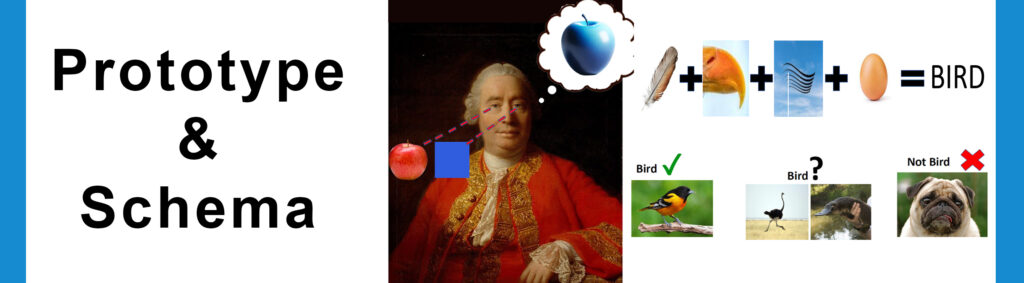

Because the AI is trained on data, and, just like a human, it has a cultural bias. You can explore why ChatGPT creates certain images by having students reflect on the images it creates. What data was ChatGPT fed that may have led to that specific image? Psychology, in regards to cognition, has a concept called a prototype: The Platonic ideal of a certain object. This prototype is built with a schema like a mathematical equation. For a bird, a schema may be: feathers + beak + flying + eggs = bird. Anything that strays to far from the prototype is more difficult to recognize for what it is. Ostriches don’t fly–are they birds? Yes, but the AI may get confused.

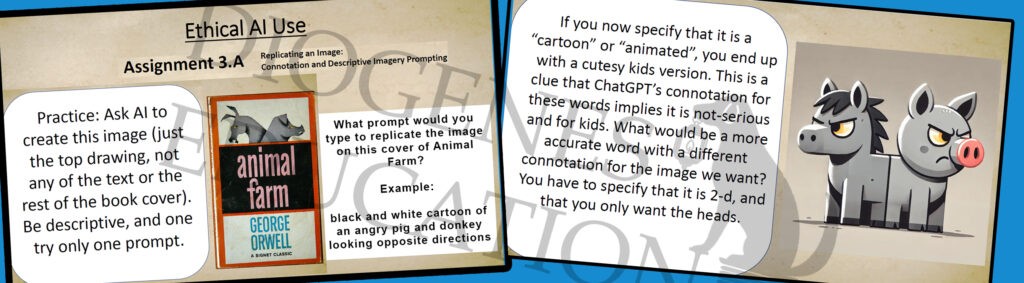

Students can create images in AI and reflect on why certain words produce certain images, such as in this Ethical AI Activities Unit. Try this now: ask for any image using the word “cartoon” or “animated” and you will end up with a cutesy, kid-friendly image.

This is a clue that, in ChatGPT’s mind, the word “cartoon” is associated with kids. ChatGPT is affected by the connotation of words because it makes “emotional” associations. Your students should ask why it is making the image-in-question based on the word choice given, and make a hypothesis as to the cultural bias, connotation, and cognition at play, analyzing the ghost in the machine.

David Hume’s Apples

David Hume says that we can only imagine what we’ve seen. You’ve seen an apple, so you can imagine an apple. You’ve seen the color blue, so you can imagine the color blue.

“But wait!” you say. “I’ve never seen a blue apple, but I can imagine one!”

True, but you’ve seen both “apple” and “blue”, and so your mind can put them together. ChatGPT is similar. It has seen a full glass of beer, and a full glass of water, and a wine glass. It can make you an image of a wine glass full of beer. It can make you an image of a wine glass full of water. It can make those only because it has seen a glass full of beer and a glass full of water, and it has seen a wine glass. But it has never seen a wine glass full of wine in all its thousands of images that taught it to create a glass of wine… But we can. What does this tell us about how its “brain” works compared to ours? Does ChatGPT know? What does an image created by ChatGPT tell us about knowledge? Does asking for the same thing in a different language change the output? Sometimes, random images seem to pop up that were not part of a prompt. Why? What other associations is it making between words? When asking for a fancy meal, a pineapple randomly appeared on the table. Why? These are the reflections students can write using AI Image generators in school for for TOK, for Psychology, and for English. The best part is that they are only making images in ChatGPT, so all the thinking and writing will be coming from them… because ChatGPT can’t write that part for them, because it cannot heed the words of the seven ancient Greek sages inscribed at the Delphic temple of Apollo: it does not know itself.

Get Started with AI Units in Your TOK, Psychology, or English Classroom

Ethical AI Activities for TOK and Psychology: Does ChatGPT Know?

Ethical AI Activities for English Classrooms

Full AP Psychology Course Bundle for the 2024 CED update

Get a FREE SAMPLE lesson Artificial Intelligence ChatGPT: Connotation, Denotation, Descriptive Imagery